We are currently closed. We will be Re-opening Last Week of November.

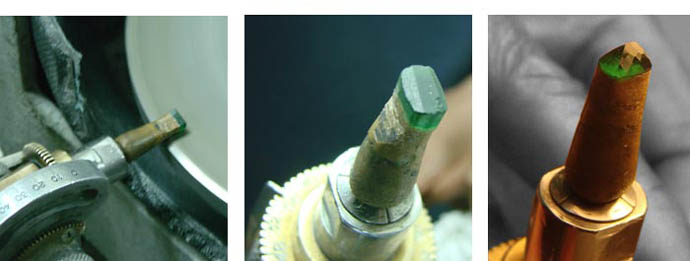

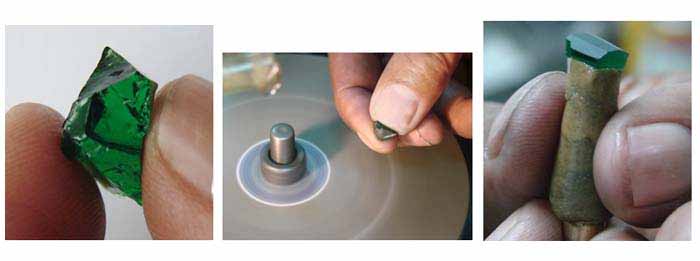

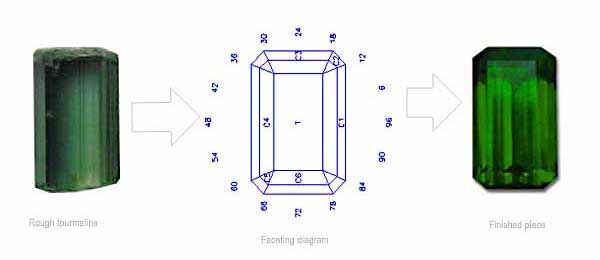

Man has been fashioning gemstones for hundreds of years in an age old quest to enhance the inherent beauty and mystery of nature's bounty. We examine the art of gem cutting and take a look at what makes a well cut gem shine.

Antony completed his GG (Graduate Gemologist) in 1998 at the Gemological Institute of America in California after a degree a Business at the University of Bath, in England. He has extensive experience in the colored gemstone trade with over 20 years buying rough at the source. He is currently the Ambassador to Kenya for the ICA (International Colored Gemstone Association) in New York which is the worldwide body for colored gemstones.

A new discovery in the renowned Taita district of Kenya has taken the gem world by storm. We take a look at the new stone and the discovery.

Some of the world's finest and rarest Rubies are now mined in Africa. The traditional sources in Asia have been depleted and there's a new kid on the block. This article delves into the fascinating world of African Rubies, where and how they are mined.

There is a great deal of misinformation currently online regarding what "ethical" Tanzanite mining is. This article explores the different opinions.

Everything you need to know about Aquamarine Gemstones. Learn all about this beautiful, rare gemstone. Learn about its properties, how to judge quality, pricing, how it is mined, where it comes from and how to spot imitations.

USA : 1 888 281 3678

USA : 1 888 281 3678 Canada : 1 888 281 3678

Canada : 1 888 281 3678  United Kingdom : 0800 368 6128

United Kingdom : 0800 368 6128 Australia : 1 800 940 788

Australia : 1 800 940 788Direct : +254 20 2641700

Office Hours 9am to 5:30pm Monday to Friday

Direct your questions about shipping, returns,

payments and any other queries

If you can't find what you are looking for in our regular collections,

submit a Special Request and let us cut / source it for you. You will be

notified by email if we find a gem that matches your specs.

Your Product has been successfully added to the cart.

Thank You for submitting a Special Request .

We will notify you by email when we find gems that match your specifications and may interest you.

You can see and manage your special requests in your account by loggin into your account and clicking on the link Special Requests.

MESSAGE SENT

We will respond shortly

ASK A GEMOLOGIST FEATURE

Terms and Conditions of Use

Use of our acclaimed Ask a Gemologist feature which affords you access to certified GIA gemologists is free of charge. However, you agree to the following tenets when you use the Ask a Gemologist feature:

1. You will be signed up as a member of theraregemstonecompany.com with all the rights and privileges of membership.

2. Questions addressed to the Gemologist panel must be related to our business. Questions unrelated to gemstones or jewelry on our website will not be answered.

FRIEND REFERRAL ADDED SUCCESSFULLY

Our system has opened them a Member's Account and sent them

an introduction email. If they purchase off the site, 6% of the sale

will automatically be credited to you EAG Account Statement

NO ITEMS FOUND WITH THAT ID

Thanks for your email .

We will reply shortly.